Stale Popcorn and Bad Data

By Scott Sanders on Nov 12, 2018 10:25 pm

If you have watched or read a news story about food in the past 10 or so years, odds are you’ve heard about one of these stories, or one of the others at the bottom of this article.

These are just a few research takeaways from Cornell University professor Brian Wansink.

When Wansink joined Cornell not long after I had graduated, I was proud to see such influential research being conducted at one of my alma maters. Wansink’s Food & Brand Lab, which occupied part of the Warren Hall office belonging to a retired former professor of mine, seemed a rather fitting—and perhaps unintentional—way to honor him. That lab was the setting of an infamous automatically refilling soup bowl experiment, which I found nefarious, insightful, and funny.

Undoubtedly, headlines like these have influenced people to think twice about how they eat. But Wansink’s research has largely been discredited, and Cornell has forced Wansink to retire.

Over the past year, many articles have questioned Wansink’s research and dissected the unquestionable errors in his techniques. The errors have been painstakingly researched by those close to academia and the analyses of the shortcomings are convincing and pervasive. (Buzzfeed broke some of the news and has comprehensive reporting.)

I think Wansink had noble intentions, creating marketable lessons to teach the general public how to eat better and be healthier. But he used sloppy techniques to draw out findings that didn’t necessarily have quantitative support, even though there were probably valuable lessons to be learned.

Wansink and his researchers had hunted through large data sets for findings to write about. They hadn’t pre-determined what those findings might be but rather crafted narratives around happenstance results.

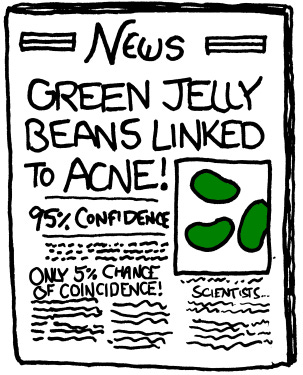

Some refer to this as p-hacking (“p” for “probability”), or data dredging; that is, finding data that appears statistically significant, even without any underlying connection. Others call this HARKing, or hypothesizing after the results are known.

The punchline from an XKCD comic: https://xkcd.com/882/

Each of these studies helps the authors accomplish their goal: academic publication. It’s the lifeblood of professors who hope to attain tenure.

But those of us outside the academic bubble who rely on those studies for guidance get mixed messages. If research is built upon shoddy foundations, how do we know which study to trust?

And there are many academic studies we hear about in the popular press, sometimes with contradictory storylines from one year to the next. I think many of them pass the simple muster of statistical significance, which allows them to be published. The authors check a box, but we don’t necessarily get good research. Wansink was a master of taking these narrow results and crafting news out of them.

In industry, my peers and I often fall into the trap of finding data to sell a narrative. We are making a case for a new item to be accepted or need to protect an item from getting discontinued. And our data is usually not held to a rigorous standard.

Wansink’s lab, on the other hand, did this in reverse: They looked for statistical importance and created narratives around those connections, though their attempts to find statistical importance were undone by mistakes that were in plain view.

I think it’s important to start with questions and hypotheses, and then let the data help understand the real story. And that data might tell a different story than the one we were hoping to find. It’s dangerous, in my view, to shortcut that process because otherwise we might convince ourselves that an untruth is true.

Here’s more Wansink studies that have great headlines.

Overeating:

People serve 22 percent more on a bigger plate than on a smaller plate.

Eating with an overweight friend will make you more likely to eat more.

Getting kids to eat well:

Eating out:

Flickr/cal222. The magic auto-refilling soup bowl.